The Florida Federal Writers Project

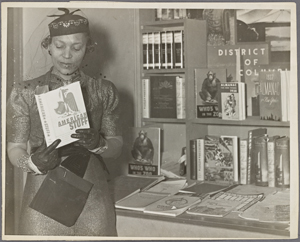

The Federal Writers Project was created in 1935 by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt as part of the Works Progress Administration. The Works Progress Administration was the centerpiece of Roosevelt’s “New Deal for America,” which put over eight million Americans back to work in the decade after the Great Depression. Some WPA programs focused on building new infrastructure or supporting agriculture, while others — including the Federal Writers Project — focused on literature and the arts. The Federal Writers Project employed out-of-work journalists, writers, teachers, and librarians in each state of the nation to create what Director Henry Alsberg (1881-1970) termed “a self-portrait of America.” Between 1935 and 1942, employees of the Federal Writers Project researched, drafted, revised, and published hundreds of books and pamphlets, including the state guidebooks, oral histories, folklore ethnographies, children’s books, local histories, and interviews with formerly enslaved Americans. It was the largest collaborative undertaking in the history of American letters.

The Florida Federal Writers Project was headquartered in Jacksonville in the Exchange Building at 214 W. Adams Street. Dr. Carita Dogett Corse (1892-1978), a historian with a PhD from Sewanee, the University of the South, served as director for the Florida project for its entire tenure. As Corse began setting up the Florida office in 1935, local African American leaders, including Mary McLeod Bethune (1875-1955), petitioned for the equal employment of African Americans in this federally-funded program. In response, Corse requested funds to hire a team of African American writers and received an initial stipend in February of 1936. On March 5, 1936 Florida became, along with Louisiana, one of the first states to employ a Negro Writers Unit, with Viola B. Muse among its first workers (Bordelon 133-34). In April, the federal office hired Sterling A. Brown, poet and an English professor at Howard University, to serve as federal editor of all materials related to African Americans. Brown guarded against the tendency to treat “the Negro as a separate entity, as a problem, not a participant in American life” and he worked to ensure that all FWP materials from the state offices would “present the Negro race adequately and without bias” (“Portrait of the Negro as American”; “American Learns”, qtd. in Stewart, 51).

The Negro Writers Unit in which Muse worked was one the largest of its kind; it was also notable for the high proportion of women employed in the unit. In addition to Muse, the project employed four other women and nine writers total: Martin Richardson, J.M. Johnson, Alfred Farrell, Wilson Rice, Rebecca Baker, Grace Thompson, Rachel Austin, and Pearl Randolph. Portia Thorington, Ruth Bolton, John A. Simms, Paul A. Diggs and Zora Neale Hurston joined after 1936. Mary McLeod Bethune was listed at the outset as a volunteer supervisor. Though Federal Writers Project employees were typically required to demonstrate financial need or unemployment status to be hired, Corse applied for an exception to this rule to staff the Florida Negro Writers Unit. Accordingly, the men and women she hired were well-educated and well-to-do.

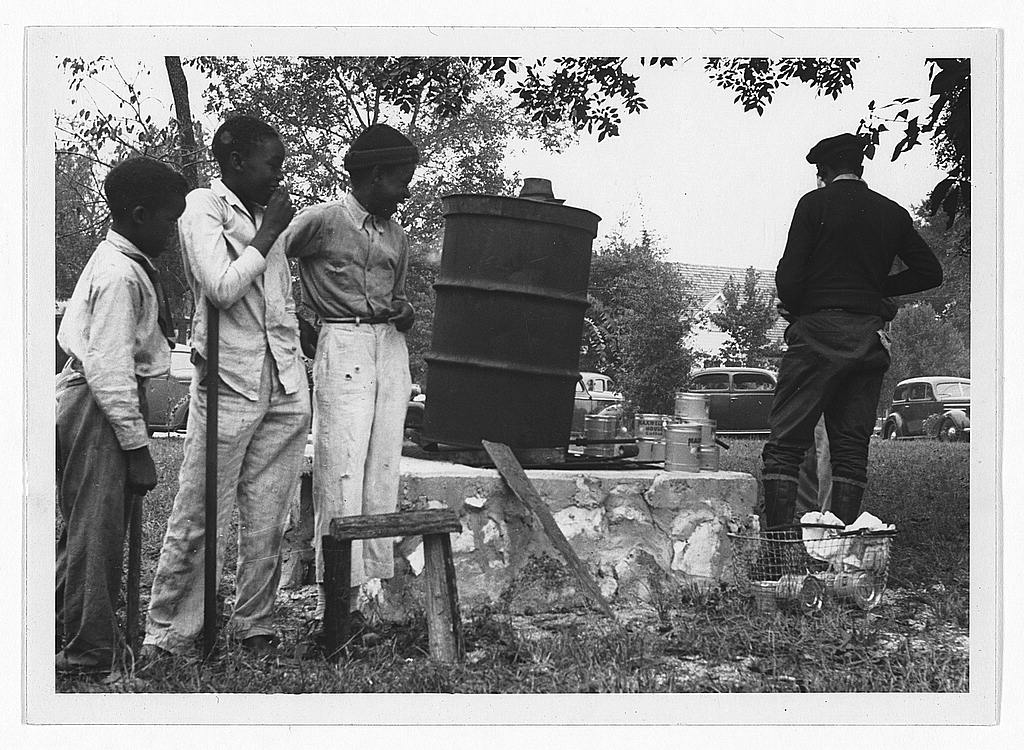

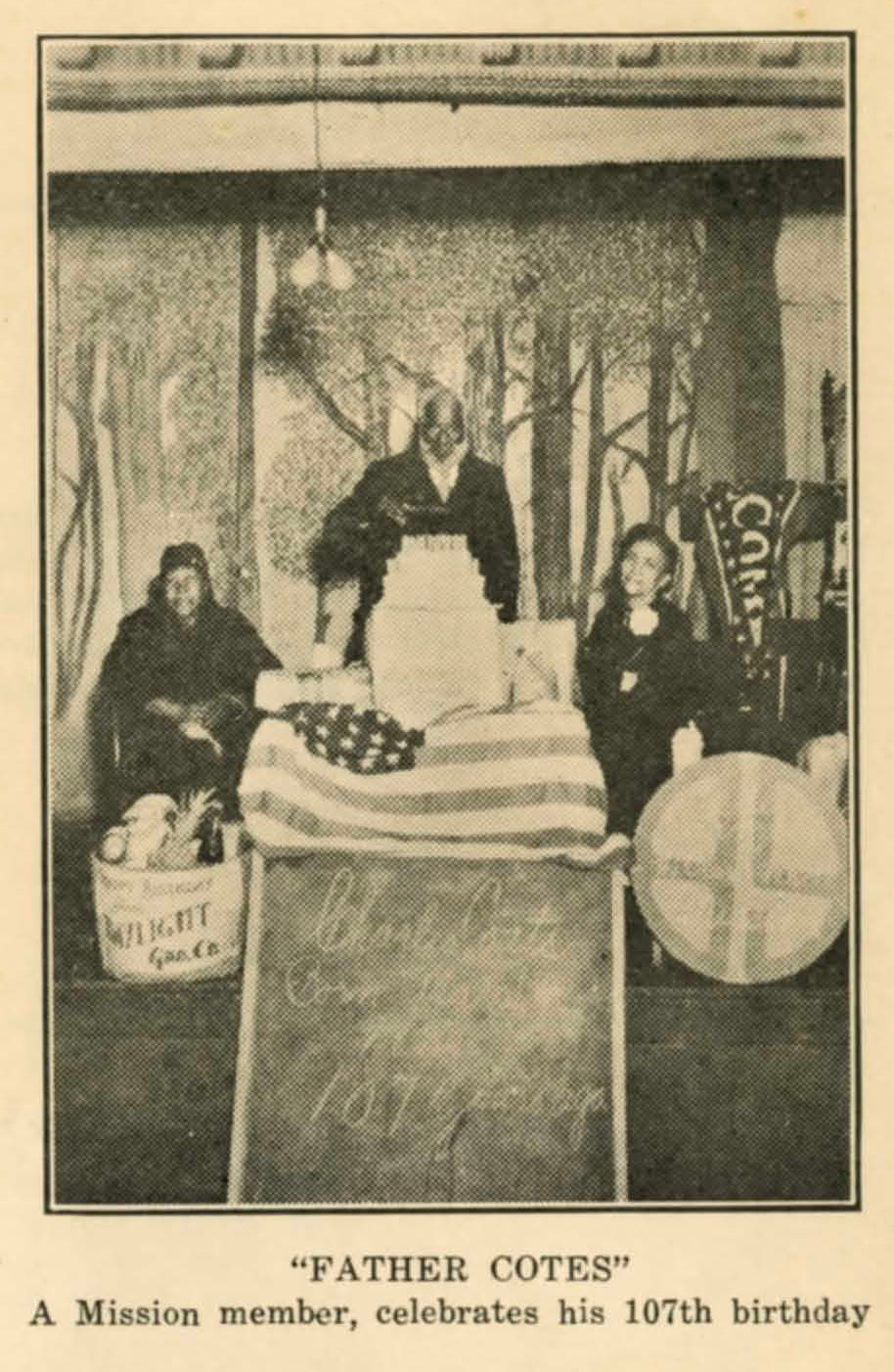

In keeping with Jim Crow segregation laws in the South, the Florida Negro Writers Unit was housed in the Clara White Mission on W. Ashley Street, apart from the main Writers Project office. The Clara White Mission was a busy place. In addition to serving three meals per day to long lines of people in need, the Mission housed Bible classes, a visiting nurse service, a day care, a sewing circle, and housed several elderly members of the community (see Stewart, 179). Jim Crow laws also limited the Black writers’ use of the research libraries and government archives to which the white writers had access; accordingly, they relied heavily on first-person interviews to gather information about Florida’s past and present from an African American perspective. In some cases, they interviewed residents of the Mission, as Muse did when she took down Charles Coates’ memories of his enslavement and emancipation (see Charles Coates Interview Notes).

Because the Florida office employed more African American interviewers and writers than almost any other state office, the quality of the information they gathered from Black Floridians was higher than that gathered about Black residents of other states – particularly when it came to collecting the experiences of formerly enslaved people. Muse was one of the first writers in the state to note the importance of conducting interviews with local residents who remembered the years before Emancipation. She wrote that “interesting tales from the days of slavery may be had for the asking” from some of the state’s “oldest Negro citizens” (“The History of the Negro in Florida,” qtd. in Bordelon, 140). In 1937, the Federal Writers Project formally initiated the “Ex-Slave Project” and credited the Florida office for showing the historical value of these interviews. Historians now agree that the Florida ex-slave narratives comprise some of the most compelling and informative narratives in the entire collection of over 2,300 interviews because they were collected almost entirely by Muse and other African American interviewers; formerly enslaved people, historian Pamela G. Bordelon writes, “spoke differently to members of their own race about their lives, their bondage, their disappointments, and their aspirations” (146).

In addition to the Ex-Slave Project, the Florida NWU produced essays on local African American literature, art, ethnography, music, religion, education, and folklore for inclusion in the Florida FWP’s planned local and state guides. A 1936 report listed their plans to produce essays on a range of topics, including “Additional slave interviews, Negroes in early Florida politics; Hoodoo practices not yet covered; Unusual Negro enterprises; Negro inventors and inventions; Sketches of successful Negroes; Survey of rural school educational methods and facilities; Survey of effects of Negro fraternal orders on social and economic life of Negroes; Survey of religious trends since 1900 including the effect of churches on present day life; Survey of economic and social status of Florida Negroes, 1863-1936; Survey of inter-racial good will” (“Progress Report,” qtd. in Stewart, 184-85). Much of this material was gathered with the intent to publish a volume on “The Florida Negro,” to match similar books in other states such The Negro in Virginia.

When the Florida Negro Writers Unit dwindled down, like many others, at the start of World War II in 1939, much of the work they had produced remained unpublished. Some of their essays had been incorporated into the state guide, Florida: A Guide to the Southernmost State. And the state office did submit the NWU’s interviews with formerly enslaved Floridians; these were processed and preserved by Benjamin A Botkin, the federal folklore editor, in the early 1940s and can be accessed today as part of the Library of Congress’s Digital Collection “Born in Slavery: Slave Narratives from the Federal Writers' Project, 1936 to 1938.” When the Florida Writers Project officially shuttered in 1942, Dr. Carita Doggett Corse oversaw the distribution of manuscript materials, including the work of the NWU, to various Florida libraries and archives, including the University of South Florida, the Florida Historical Society, Jacksonville University Swisher Library, and the University of Florida P.K. Younge Library. In 1993, Gary W. McDonogh assembled some of these documents in order to finally publish The Florida Negro: A Federal Writers Project Legacy, based on the earliest drafts of that monograph. But many other documents produced by the Florida NWU, including the Viola Muse Collection, have never been fully assembled and published.

Works Cited

“American Learns of Negro from Books of the Federal Writers Project,” March 6, 1939, Entry 27, Box 1, File “Releases and Information on FWP,” Record Group 69, Federal Writers’ Project, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

Bordelon, Pamela G. The Federal Writers’ Project’s Mirror to America: The Florida Reflection. Louisiana State University HIstorical Dissertations and Theses, 1991.

Brown, Sterling A. “Portrait of the Negro as American.” Box 210, Federal Writers’ Project Files, Works Progress Administration records, Record Group 69, Federal Writers’ Project, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

Federal Writers Project, “The History of the Negro in Florida,” (unpublished manuscript, P. K. Yonge Library of Florida History, Gainesville).

Florida: A Guide to the Southernmost State. Compiled by Federal Writers' Project of the Work Projects Administration for the State of Florida. Oxford University Press, 1939.

McDonough, Gary W. The Florida Negro: A Federal Writers Project Legacy. University Press of Mississippi, 1993.

The Negro in Virginia. Compiled by the Writers Program - Virginia. Hastings House, 1940.

“Progress Report, Negro Unity, Federal Writers’ Projects,” December 16, 1936. Entry 13, Box 8, File “Florida Edictorial Misc., 1935-36,” Record Group 69, Federal Writers’ Project, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

Stewart, Catherine A. Long Past Slavery: Representing Race in the Federal Writers’ Project. University of North Carolina Press, 2016.