LaVilla

LaVilla began as a Gullah Geechee community in 1866 when “Francis F. L’Engle subdivided a portion of J. McRobert Baker’s former LaVilla plantation and provided 99-year leases to 41 freedmen” (The Jaxon). LaVilla existed as a distinct, majority Black town with its own mayor until it was annexed into Jacksonville in 1887. Further growth came in 1897 when Henry Flagler began the Jacksonville Terminal Company and opened a Union Depot in the area.

The first Jacksonville Terminal building was built in 1898 and the current building (now the Jacksonville Convention Center) was completed in 1919, bringing not only passengers but also railway workers to the neighborhood. In fact, LaVilla was home to the largest passenger railroad station south of Washington, D.C. In 1925, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters was founded, with Jacksonville’s A. Philip Randolph serving as the organization’s first president. The Pullman Company was one of the largest employers of Black citizens in the nation, and its workers—Pullman Porters—were among those forming a growing Black middle class. Also living in the area were many workers—namely cooks and waiters—from downtown’s Hotel George Washington, the first 100% air conditioned hotel in the nation, which opened in 1926.

Also emerging in the neighborhood were religious institutions and social service agencies. The Bethel Baptist Institutional Church (now The Bethel Church) was founded in 1838 and built its permanent structure in 1861 at the corner of Church and Julia streets. Althouch historically Black, the church was interracial until after the Civil War and Emancipation when white members segregated themselves, forming what later became First Baptist Church.

Also located in LaVilla is the Clara White Mission, which Eartha M.M. White founded in 1904 to offer services to Black residents that were not offered by the city of Jacksonville. Since the 1880s, White’s mother, formerly enslaved Clara English White, had been feeding her neighbors, thus beginning some of the work Eartha M.M. White would later expand through the mission.

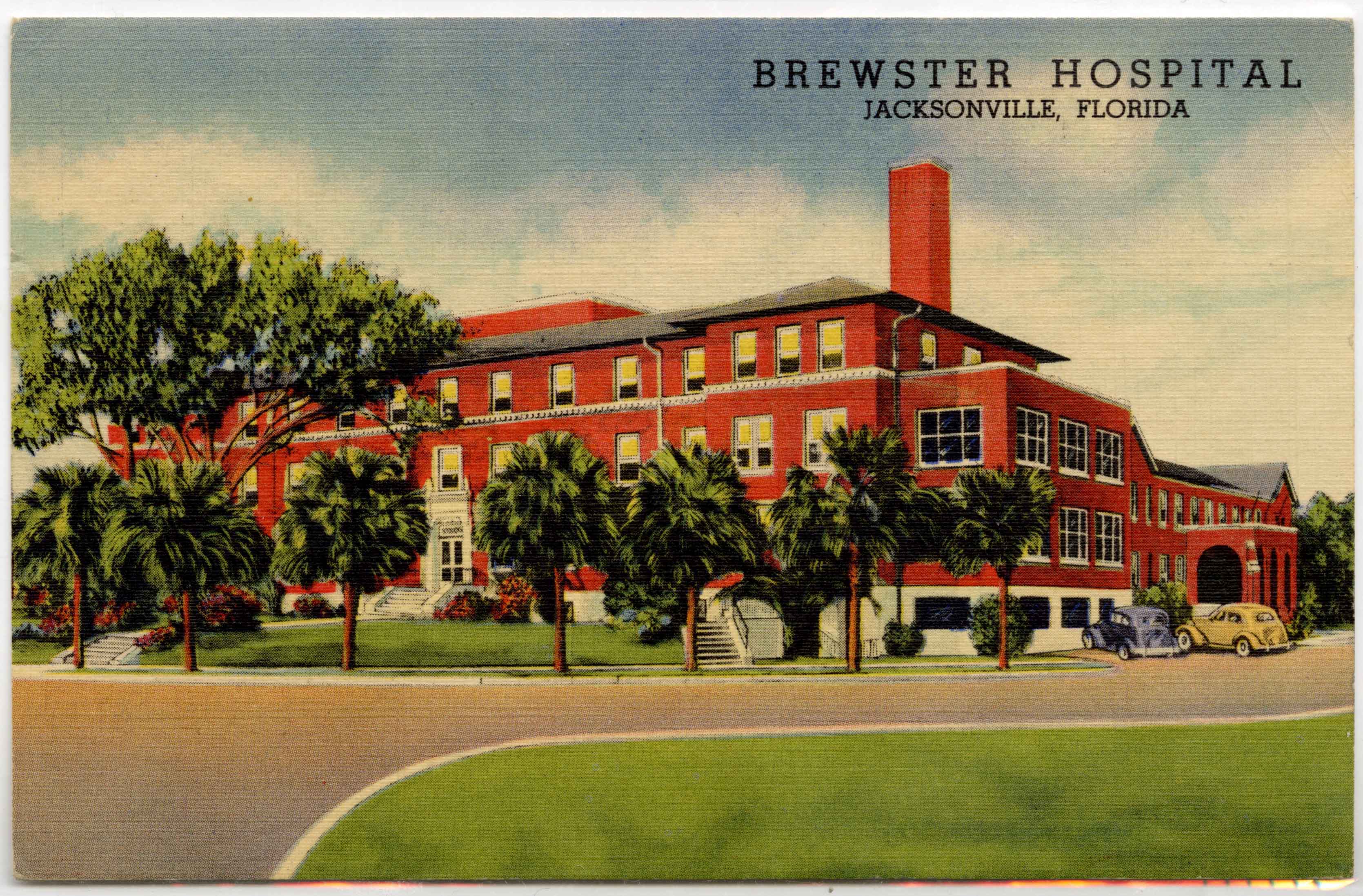

Similarly, Brewster Hospital was the first hospital in the city for Black residents. Initially located at 915 West Monroe Street, the hospital was opened in 1901 by the Women’s Home Missionary Society of the Methodist Church. It subsequently moved to 7th and Jefferson Streets, now the site of Methodist Hospital. Brewster also housed a nursing school that was affiliated with the Boylan-Haven Industrial Training School for girls and served as the first training hospital for African Americans in the United States. It closed in 1966 after desegregation allowed Black citizens to receive medical care at other local hospitals.

In addition to facilitating businesses and social services, LaVilla became an entertainment hub. During the early 20th Century, LaVilla gained a reputation as the Harlem of the South since it was the winter headquarters of the Chitlin Circuit, the name given to a string of Black-owned theaters, night clubs, music venues, and juke joints where Black entertainers could safely perform during the Jim Crow era of segregation. The circuit included venues in major cities like Detroit, Chicago, New York’s Harlem borough, Washington, D.C., and Atlanta as well as numerous other cities, including Jacksonville. Local venues included the Ritz Theatre on Davis Street and the Bijou Theatre on Ashley Street (now the Clara White Mission), among others, and playing these venues were well known performers such as Ma Rainey, Louis Armstrong, and Duke Ellington. Black entertainers, celebrities, and business tycoons would also vacation at nearby “Black” beaches such as American Beach on Amelia Island and Manhattan Beach (established in 1901), which became Hanna Park.